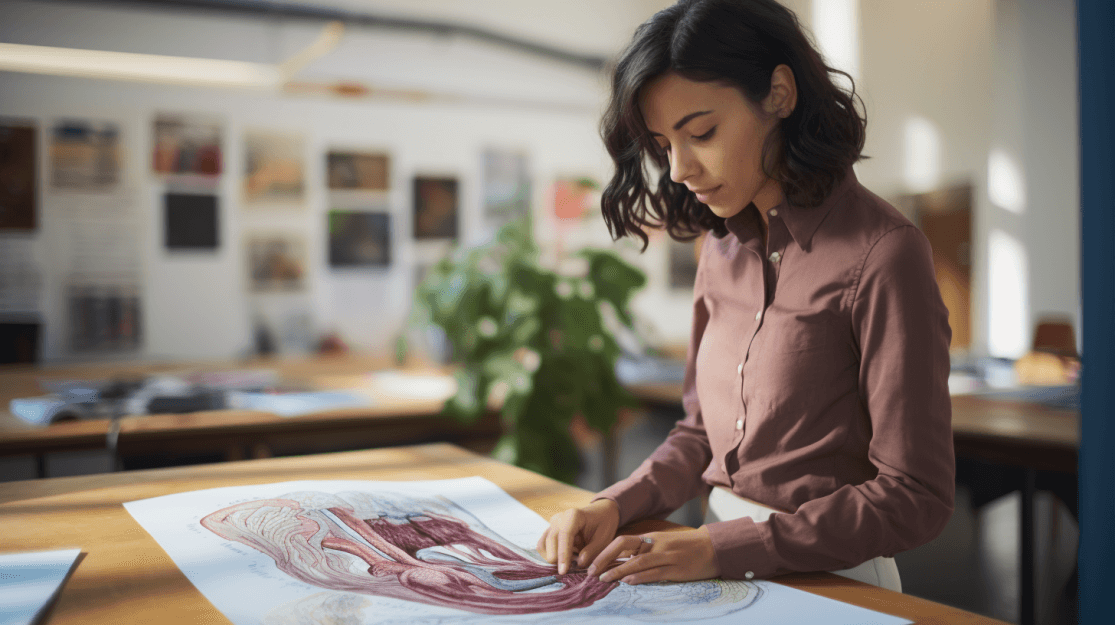

The Digestive Process: An Overview

From the moment we take a bite, our body gets to work. Digestion involves several stages: ingestion, propulsion, mechanical digestion, chemical digestion, absorption, and elimination. The food undergoes a transformative journey, becoming smaller molecules our cells can utilize.

Mouth: The Starting Point

Not only the beginning of the digestive process, but the mouth also plays a significant role in both mechanical and chemical digestion. As we chew, the teeth break down food into manageable pieces. Simultaneously, salivary glands produce saliva, which contains amylase, an enzyme that initiates carbohydrate digestion by converting starches into simpler sugars. Interestingly, the process of chewing itself triggers more digestive reactions downstream, preparing the stomach and intestines for incoming food.

Esophagus: The Pathway Down

Beyond being a mere conduit, the esophagus uses coordinated muscle contractions, or peristalsis, to transport food. As food reaches the end of the esophagus, the lower esophageal sphincter ensures a one-way passage, preventing the acidic contents of the stomach from flowing backward, thus preventing acid reflux. The esophagus is lined with mucus-producing glands, which lubricate the tube, aiding in smoother food movement.

Stomach: A Chemical Cauldron

The stomach is a dynamic organ, both a reservoir and an initiator of further digestion. Once food is inside, the stomach releases hydrochloric acid and the enzyme pepsin to create an acidic environment essential for protein breakdown. Additionally, the stomach's rhythmic contractions mix food with these secretions, producing a semi-liquid substance called chyme. This chyme is then gradually sent to the small intestine for additional processing.

Small Intestine: The Hub of Nutrient Absorption

The small intestine is the primary site for the absorption of nutrients. As chyme enters the duodenum, the first segment, it's mixed with bile from the gallbladder and digestive enzymes from the pancreas. These substances help break down fats, carbohydrates, and proteins further.

The majority of nutrient absorption, including sugars, amino acids, and fatty acids, takes place in the jejunum, the second part of the small intestine. The inner surface of the small intestine is lined with tiny, finger-like projections called villi and microvilli. These structures increase the surface area for absorption, ensuring maximum nutrient uptake.

Vitamins are also absorbed in the small intestine:

Water-soluble vitamins (such as vitamin C and B-vitamins) are absorbed directly into the bloodstream.

Fat-soluble vitamins (A, D, E, and K) require bile acids to form micelles and are then absorbed in the ileum, the final part of the small intestine.

Large Intestine: Water Retrieval and Waste Formation

The large intestine's primary role is to absorb water and electrolytes from the remaining indigestible food particles, transforming liquid waste into stool. One of the most fascinating aspects of the large intestine is its rich microbial ecosystem. Housing trillions of bacteria, known collectively as the gut microbiota, the colon plays a pivotal role in our overall health. These beneficial microbes aid in breaking down food residues, especially dietary fibers, that our bodies can't digest on their own. In this symbiotic relationship, the bacteria produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) such as butyrate, propionate, and acetate, which are vital energy sources for our colon cells and contribute to several essential bodily functions. Furthermore, the balance and diversity of these microbes can significantly impact our immune responses, metabolism, and even our mood. In essence, the colon doesn't work alone but rather thrives on the collaborative efforts of these numerous microorganisms.

Rectum and Anus: The Final Exit

Acting as storage before elimination, the rectum holds onto waste until we're ready to expel it. The complex coordination between involuntary and voluntary muscles in the rectum and anus allows for controlled defecation. The body possesses specialized sensors in this region, helping us differentiate between solid, liquid, and gas, ensuring we can respond appropriately.

Associated Organs: The Helpers in Digestion

Liver: Often termed the body's chemical factory, the liver detoxifies various metabolites, synthesizes proteins, and produces bile, crucial for fat emulsification and digestion.

Gallbladder: Serving as a storage pouch, the gallbladder concentrates and releases bile into the small intestine upon food's presence, especially fats.

Pancreas: A dual-function gland, the pancreas releases digestive enzymes and regulates our blood sugar by secreting insulin.

Kidneys: While primarily known for their role in filtering blood, removing waste, and balancing bodily fluids, the kidneys also play a part in digestion. They are responsible for the reabsorption of water, glucose, and amino acids, and the secretion of waste products into the urine. Additionally, they regulate the balance of electrolytes like sodium, potassium, and calcium – vital elements for muscle function and other bodily processes.

Conclusion

The journey of food through our digestive system is a masterclass in biological efficiency and coordination. With each bite, a series of intricate processes commence, providing our bodies with the vital energy and nutrients needed for survival. By understanding this remarkable system, we're better equipped to make informed decisions about our diet and health.

To learn more about optimizing your digestive health and overall well-being, explore Intea's Gut Health Reset program at inteahealth.com.

Sources:

Marieb, E. N., & Hoehn, K. (2018). Human Anatomy & Physiology. Pearson Education.

Carpenter, G. H. (2013). The secretion, components, and properties of saliva. Annual Review of Food Science and Technology.

Edgar, M., Dawes, C., & O'Mullane, D. (2004). Saliva and Oral Health (4th ed.). Stephen Hancocks.

Pandolfino, J. E., & Kahrilas, P. J. (2013). Esophagus: Anatomy, physiology, and motility. Clinics in Chest Medicine.

Karam, S. M. (1993). Dynamics of epithelial cells in the corpus of the mouse stomach. Anatomy and Embryology.

Dressman, J. B. (1986). Comparison of canine and human gastrointestinal physiology. Pharmaceutical Research.

Helander, H. F., & Fändriks, L. (2014). Surface area of the digestive tract – revisited. Scandinavian Journal of Gastroenterology.

Flint, H. J., Scott, K. P., Duncan, S. H., Louis, P., & Forano, E. (2012). Microbial degradation of complex carbohydrates in the gut. Gut Microbes.

Sun, W. M., & Read, N. W. (1990). Motor functions of the rectum and anus. Critical Reviews in Clinical Laboratory Sciences.

Geier, A., Fickert, P., & Trauner, M. (2017). Mechanisms of disease: mechanisms and clinical implications of cholestasis in sepsis. Nature Clinical Practice Gastroenterology & Hepatology.

Apte, M. V., Wilson, J. S., & Korsten, M. A. (1997). Alcohol-related pancreatic damage: mechanisms and treatment. Alcohol Health & Research World.

Sender, R., Fuchs, S., & Milo, R. (2016). Revised estimates for the number of human and bacteria cells in the body. PLoS Biology.

Den Besten, G., van Eunen, K., Groen, A. K., Venema, K., Reijngoud, D. J., & Bakker, B. M. (2013). The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. Journal of Lipid Research.

Cryan, J. F., & Dinan, T. G. (2012). Mind-altering microorganisms: the impact of the gut microbiota on brain and behaviour. Nature Reviews Neuroscience.

Schrier, R. W. (2014). Renal and Electrolyte Disorders. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins.

Your 14-Day Journey to Gut Health Begins Now!

Don't let digestive issues hold you back any longer—take the first step towards a healthier, happier you today